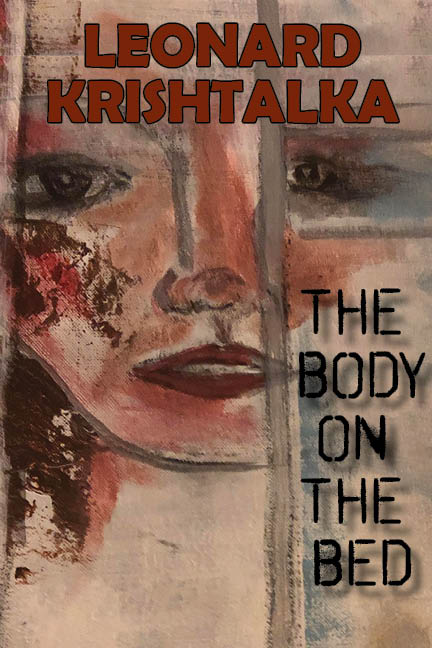

THE BODY ON THE BED

Murder in post-civil war Lawrence, Kansas. Based on court trial transcripts from 1871, this historical novel tells the murderous tale of desire, poison and devious betrayal as investigated by Mary Fanning, the first woman reporter west of the Mississippi …

From the Notes of Mary Fanning:

I became a Tribune correspondent today—as Mary Fanning. “Apitz” is Frederick’s surname. I’ve always despised it. The rawness of the sound, almost painful, like a wound. “Apitz” comes from “spitz.” It is German for “sharp” or “point,” like a crude stick to poke out an eye. I have kept it from being annealed to my name. Worse than the sound, it smacked of chattel. I was Mary Eliza Fanning at birth, Fanning in childhood, and Fanning when I married at twenty-two. Fanning it will stay.

I warned Frederick of this. He pretended not to hear. He thought it would pass, like a winter colic. It didn’t.

He’s been away since Thursday, in Texas selling hides. He will not be pleased when he returns and learns that my views will now be public, in a newspaper. Julia will be proud. She’ll be here with me this afternoon.

Speer is enlightened. He tells me I am the first woman journalist west of the Mississippi, and only the second west of the Hudson. Mary Ames writes a column, “A Woman’s Letter From Washington,” for the Independent in New York. Yet another ‘Mary.’

I asked Speer whether I should reveal in the Tribune what Frederick saw last Wednesday night when Mr. Ruthman died. Frederick came home from work about eleven o’clock and noticed the light in Isaac’s bedroom. The curtain was partially raised. Isaac was sitting on the bed, still dressed in his shirt and vest. But he was bent over, his hands clasped around his stomach, his face contorted in apparent pain. Alarmed, Frederick said he started toward Ruthman’s door, but stopped almost instantly. He thought there was someone else in the bedroom, a man standing in the shadows in the front corner. Frederick couldn’t see his face. It was hidden by the curtain. Was it Medlicott?