A diabolical murder mystery: dead archeologist, two robbed graves, a lover’s trial, a bloody journal, a mummified Neandertal child, and a stunning revelation.

A major theme I’ve explored in my novel, The Camel Driver, which was published in November 2020, is the initial role that anthropology, biology and natural history museums played in promoting systemic racism. This theme is manifest in the story—the sin and redemption of a taxidermist who robs the graves of indigenous people and prepares them—taxidermies them—for human exhibits in museums and salons in 1800s Europe.

The story weaves in and out of one of those exhibits, a world-famous diorama at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh formerly called Arab Courier Attacked by Lions. It depicts a North African drama: A “courier,” dressed in traditional clothing, is crossing the Sahara Desert on a dromedary camel, when they are suddenly set upon by two ferocious Barbary lions. The courier has managed to grab his single-shot rifle and kill the lioness, who had attacked from the front. The male lion has leapt onto the camel from the side, burying his claws into the camel’s foot and hump, slowly pulling him down. The courier has pulled out his dagger and is about to plunge it into the lion’s throat. At the same time, the lion has lunged at the courier and is about to bite off his arm. We don’t know who wins this epic struggle. As with art, the verdict is in the mind of the viewer.

Arab Courier, now renamed Lion Attacking a Dromedary, has recently generated enormous controversy. For the past 120 years, it has been the second most popular display at the Carnegie. A few years ago the Carnegie X-rayed the mount and was shocked to discover that under the courier’s head dress is his real skull and teeth. The museum promptly draped it from public view, because human remains in a museum exhibit denigrates the people and culture of that individual. It also implies that grave-robbing and human taxidermy are acceptable in our museum displays and in the exhibiting of science and art.

Jules Verreaux, the French taxidermist who created Arab Courier, is infamous for this sort of museum work. He was a naturalist and wildlife merchant at his father’s natural history emporium in Paris, and later at France’s national museum of natural history. Verreaux likely obtained the skull and skeleton of the courier by robbing a grave in North Africa, perhaps in the same region where he collected the two Barbary lions for the exhibit. Then he taxidermied the human, the lions, and the camel, and mounted the dramatic scene of the attack over a bed of sand to simulate the desert landscape. He entered Arab Courier in the 1876 Paris Exposition. It won the gold medal.

Arab Courier is a creation of its time: in its makeup and history, it encompasses the racist ideas of the 1800s and 1900s that were broadcast to the world by European culture—by museums, zoos, and world fairs; by art, literature, theater and cinema; and by anthropology and biology taught in colleges and universities.

He was displayed throughout France, then at the 1888 Barcelona World’s Exposition, and then sold to a private museum in Banyoles, Spain, north of Barcelona, where he remained on exhibit until as late as 1990. Eventually, the Spanish government became concerned about international embarrassment over such a racist exhibit, but only because the 1992 Olympics were coming to Barcelona. So, against fervent protests from the mayor and townspeople of Banyoles, they forced repatriation of the chieftain to Botswana.

For example, fifty years earlier, in the 1826, during a wildlife collecting expedition to what is now Botswana, Verreaux and his brother, Eduoard, robbed the grave of a Botswanan chieftain who had died two days earlier. They skinned him, shipped his skin, skull and skeleton to their emporium in Paris, taxidermied him, and mounted him in a glass display case wearing an antelope cloth and clasping an orange shield and a barbed spear. They called the exhibit, “El Negro.”

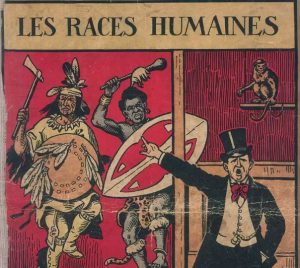

Tree of human races. Photo by Leonard Krishtalka

The Banyoles museum is now silent about their “El Negro” exhibit. It is not mentioned in any of their brochures and none of the employees will talk about it. “El Negro” was only one of hundreds such despicable exhibits of native peoples from the colonies depicted as savages, subhuman, and inferior to white Europeans.

In 1831, the Paris Colonial Exposition featured a “human zoo” of indigenous people, Melanesians from New Caledonia in the South Pacific. It attracted 24 million visitors over six months. The U.S. participated in these depraved racist displays. In 1904, six Mbuti natives from the Congo were purchased by an American businessman, Samuel Verner, and put on display at the St. Louis World’s Fair as living examples of an ape-like stage of human evolution. Five of them died of disease.

After the fair closed, the surviving Mbuti,named Ota Benga, was brought to New York and displayed as an African savage in the Hall of Anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History. In 1906 the Bronx Zoo in New York bought Ota Benga, shoved him in a cage with an orangutan, and hung up a sign that said: MISSING LINK. Ota Benga eventually committed suicide.

The last human zoo, advertised as Kongorama, was held at the 1958 Belgian World’s Fair. Remember that Emperor Leopold II owned the Congo, brutalized and enslaved its people, and mined its resources. Kongorama was a makeshift village of straw huts set in a tropical garden and encircled by a bamboo fence. Every day, Congolese families—women, men, children—forcibly imported from the Congo, were clothed in traditional dress and trotted out to do chores to the amusement of spectators, who tossed bananas and peanuts into the enclosure.

As the detective in The Camel Driver says, “Exhibits tell the bigotry of their time.” How did these racist ideas form and become incorporated into museums, zoos, world fairs, and other cultural media?

The origins of this racism––that whites were the superior race and all other peoples were inferior––goes back at least 250 years to the 1700s and early 1800 during the Enlightenment revolution in Europe. There’s two things to remember about the Enlightenment. One is the good, the other is ugly.

First, the good. The Enlightenment was a revolution that freed us from medieval thinking about who we are and how the Earth and its life arose. It replaced superstition and myth with our modern ideas of individual liberty, reason, democracy, free-will, and inquiry. Much of what we call science today was born then.

Now for the ugly. The heyday of the Enlightenment was also the heyday of European colonialism in Africa, Asia, Australia, India, and the Americas. When the European explorers, merchants and settlers encountered the native peoples in the colonies they were immediately judged to be primitive, savage, and subhuman, not capable of the liberty, reason, democracy and culture that defined European Enlightenment thinking. Being classified as subhuman, this justified the wholesale subjugation, enslavement, and killing of the native peoples by the European powers.

And anthropology and biology gave its scientific stamp of approval to this racism. Anthropology—the study and classification of humankind—became a full-blown theory of race and racial superiority. One of the Enlightenment’s heralded philosophers, Immanuel Kant, put it bluntly in his 1798 anthropological treatise:

“Humanity exists in its greatest perfection in the white race – The yellow [race] have a smaller amount of Talent. The Negroes are lower and the lowest are – the [Native] American peoples.”

In effect, people’s skin color alone became the measure of intellectual capacity. People’s physical traits pointed to their assigned place on Nature’s “tree of life” between apes and European Caucasians—the white race—which constituted the ideal. They were followed in increasingly diminished biological and cultural development by “Mongolians, the yellow race,” “Malayans, the brown race,” “Ethiopians, the black race,” and “Americans, the red race.” This idea of racial ranking and superiority became the canon, thought to be humanity’s natural order.

This racist virus became our cultural pandemic. It infected generation after generation through science, art, literature, history, education, entertainment, film, world’s fairs, zoos, and museums. It suffused society and our consciousness. It became systemic.

The obvious question now is, what to do? The answer, I think, lies in how Verreaux achieved redemption in The Camel Driver. Through his own grave-robbing and taxidermy for human exhibits––the skinning and dissection and stuffing of the native individuals––he discovered that all he had been taught by scientific luminaries and society about native peoples and their alleged racial ranking and racial inferiority was complete BS. With this realization, he designs the Arab Courier exhibit to demonstrate racial equality in physical and mental traits.

This translates to the larger scale of the museum community and all other cultural media. First, they need to own up to and face their complicit past in the 1800s and 1900s. Second, biology, anthropology, and much of popular culture have since disproven, disowned, and repudiated any and all notions of race and racial superiority. Museums can and should deploy the very collections once used to broadcast racism to teach what we got wrong then, why we got it wrong, and what we now know to be right about native peoples and their cultures.

For example, at the Carnegie Museum, the Arab Courier diorama can be undraped to provide a powerful teaching moment about the Verreaux natural history emporium in Paris, why they created appalling exhibits of African native peoples, and what does current knowledge tell us about these peoples, their cultures, and their ways of life.

Museums have three powerful weapons to advance this agenda. They have the knowledge––the artifacts and exhibits for these teaching moments. They have the potency––hundreds of millions of visitors in their public galleries, and their online and social media platforms and community outreach programs. And they have the public trust: all polls show that people trust the information they get in museums more than from any other medium.

With these three weapons––knowledge, potency and trust––museums worldwide can help exorcise the systemic racist memes from our cultural consciousness.

Leonard Krishtalka is the author of award-winning essays, the acclaimed book, Dinosaur Plots, and the Harry Przewalski series of mystery novels, The Bone Field, Death Spoke, and The Camel Driver. As a paleontologist, he has explored the fossil-rich badlands of the American West, Canada, China, Patagonia, Kenya, and Ethiopia––inspirations for the intrigues of science and murder. His next book, The Body on The Bed, is forthcoming.